Imbalance in the scientific literature

In a new paper published in the Journal of Developmental Origins of Health and Disease, Debbie Lawlor, Sarah Richardson, Laura Schellhas and I show that there have been more studies of maternal prenatal influences on offspring health than any other factors.

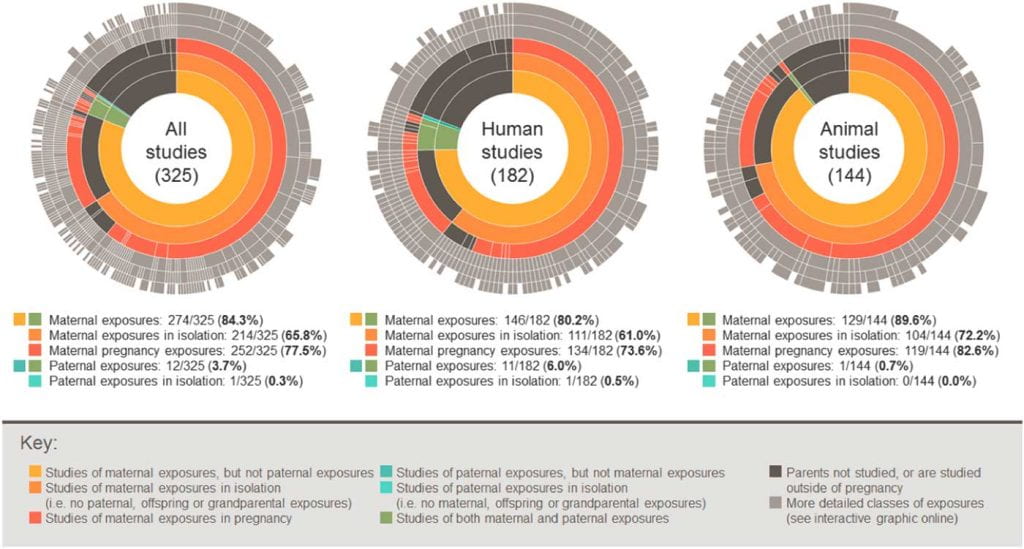

We took all the studies that have been published in the journal since it began nearly a decade ago and categorised them based on the things they studied. You can visualise the results here.

Assumptions about the “causal primacy” of maternal pregnancy effects

This work builds on an article we wrote last year where we argue that this focus on maternal pregnancy effects has come about because people assume that mothers are the single most important factor in shaping a child’s health.

But is this assumption true? You can read more in a blog I wrote earlier this year for WRISK (spoiler: I don’t think it is).

https://www.wrisk.org/uncategorized/its-the-mother-is-there-a-strong-scientific-rationale-for-studying-pregnant-mothers-so-intensively/

Why is this a problem?

This assumption, and the resulting imbalanced research, means that we might be missing other factors that could be easier to change to improve child health. For example, paternal or postnatal factors might lessen or increase the effect of any maternal or pregnancy factor, or might be important factors independently of maternal exposures.

Although well-meaning, complex scientific findings about maternal effects are being used to provide simplified health advice to women about what they should and shouldn’t do during pregnancy. This feeds into public beliefs about how pregnant women should behave, which can limit their freedom and negatively affect their experience of pregnancy and parenting.

What are we doing about it?

To create more of a balance, in our paper we call for more research on how child health might be influenced by fathers and other factors, including the social conditions and inequalities that influence health behaviours. We also call for greater attention to be paid to how health advice to pregnant women is constructed and conveyed, with clear communication of the supporting scientific evidence to allow individuals to form their own opinions.

By studying maternal AND paternal factors, the EPoCH study will help highlight whether attempts to improve child health are best targeted at mothers, fathers or both parents. We’ll work closely with organisations like WRISK to ensure our results are communicated effectively and sensitively to avoid blaming parents.